Understanding Energy Deficit in Human Physiology

Educational content only. No promises of outcomes.

Understanding Energy Deficit Physiologically

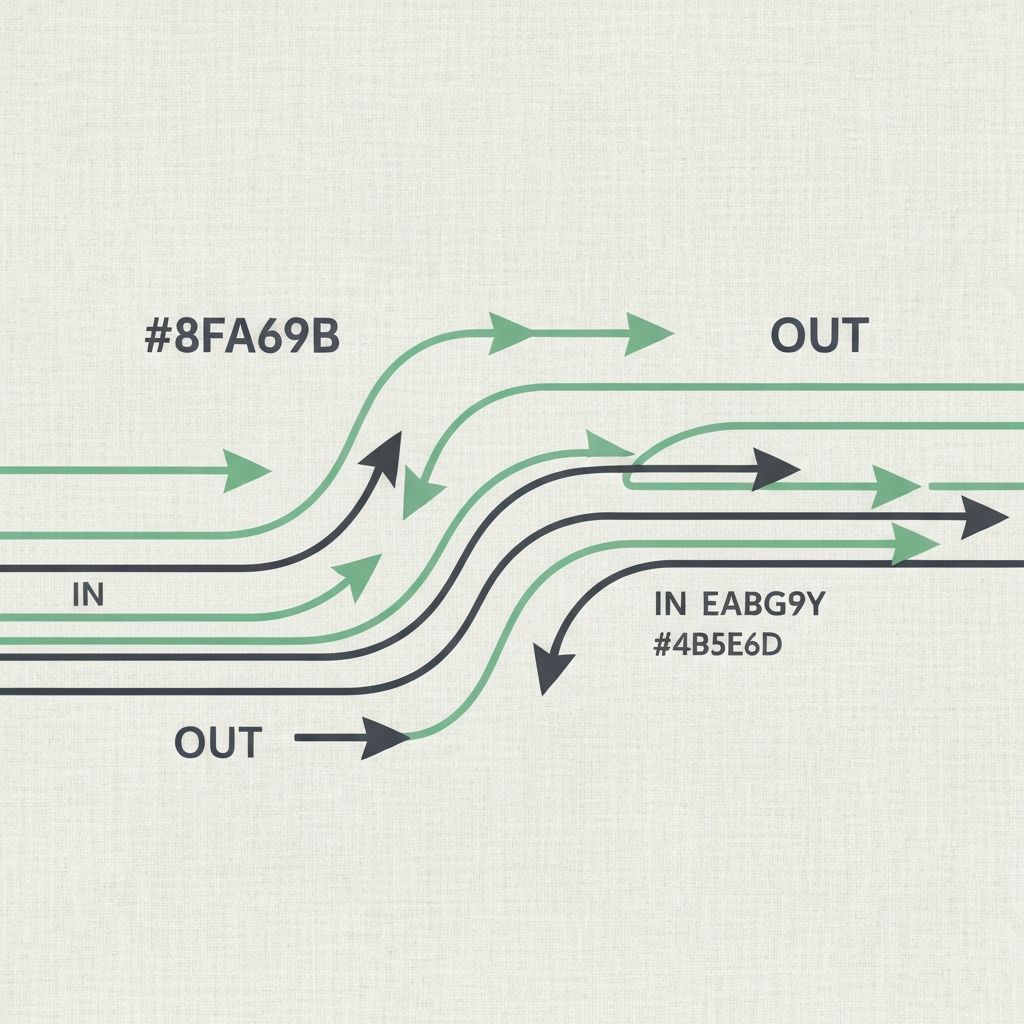

An energy deficit occurs when the total energy expenditure of the human body exceeds the total energy intake from food. This fundamental imbalance triggers a cascade of physiological responses designed to adapt to reduced energy availability.

At the most basic level, energy balance can be expressed as:

Energy Balance = Energy Intake - Energy Expenditure

When expenditure exceeds intake, the body enters a state of negative energy balance, commonly referred to as an energy deficit. Understanding this concept requires examining the components of energy expenditure and how the body responds to sustained reductions in caloric intake.

Components That Contribute to Energy Expenditure

Total daily energy expenditure consists of four primary components:

| Component | Description | Approximate % of TDEE |

|---|---|---|

| Basal Metabolic Rate (BMR) | Energy required for essential physiological functions at rest: respiration, circulation, cell production, nutrient processing | 60-75% |

| Thermic Effect of Food (TEF) | Energy expended during digestion, absorption, and processing of nutrients; varies by macronutrient composition | 8-15% |

| Non-Exercise Activity Thermogenesis (NEAT) | Energy expended during daily activities: occupational activities, fidgeting, spontaneous movement, maintenance of posture | 15-30% |

| Exercise Activity Thermogenesis (EAT) | Energy expended during structured, intentional physical activity and exercise | 5-10% |

Each component is subject to individual variation and adaptation, particularly in response to prolonged energy deficit.

How the Body Detects and Responds to Reduced Intake

The body possesses sophisticated mechanisms for detecting changes in energy availability. When caloric intake decreases, several hormonal and neural signals initiate adaptive responses:

Leptin, produced by adipose tissue, decreases with reduced energy intake, signaling energy scarcity to the central nervous system. This decrease triggers increased appetite and initiates metabolic adjustments.

Ghrelin, a hormone produced primarily in the stomach, increases during energy deficit, promoting hunger and food-seeking behavior.

Thyroid hormones (T3 and T4) may decrease, leading to reductions in metabolic rate as part of adaptive thermogenesis.

Cortisol levels may rise, influencing nutrient partitioning and contributing to metabolic adaptations.

These coordinated hormonal changes represent the body's attempt to restore energy balance by simultaneously increasing energy intake drive and reducing energy expenditure.

Adaptive Thermogenesis Explained

Adaptive thermogenesis, also termed metabolic adaptation or adaptive thermogenesis, refers to the decrease in energy expenditure that occurs in response to sustained caloric restriction. Research demonstrates that this adaptation extends beyond simple reductions in BMR.

Primary mechanisms include:

- Reduction in sympathetic nervous system activity, decreasing metabolic rate

- Downregulation of thyroid hormone production and peripheral conversion

- Decreased energy expenditure at rest due to reduced metabolic enzyme activity

- Spontaneous reductions in NEAT as the body conserves energy through reduced movement

- Alterations in muscle protein turnover to preserve lean mass

The magnitude of metabolic adaptation varies among individuals and is influenced by factors including the severity of the deficit, its duration, baseline metabolic rate, and genetic predisposition. Research suggests that deficits of greater severity may trigger more pronounced adaptive responses.

Influence of Macronutrient Composition

While total energy deficit is the primary determinant of energy balance, the macronutrient composition of food consumed influences several physiological outcomes:

Carbohydrates

Carbohydrates have a TEF of approximately 5-10%. They are the primary fuel source for the central nervous system and are readily oxidized during physical activity. Carbohydrate restriction may increase perceived fatigue during activity due to glycogen depletion.

Protein

Protein possesses the highest TEF among macronutrients (20-30%), meaning a larger proportion of calories consumed from protein are expended during digestion. Adequate protein intake during deficit may support preservation of lean mass through maintenance of muscle protein synthesis rates.

Fat

Fat has the lowest TEF (0-3%) and is energy-dense, providing 9 calories per gram compared to 4 calories per gram for carbohydrates and protein. Adequate fat intake supports hormone production and nutrient absorption of fat-soluble vitamins.

Role of Physical Activity in Deficit Dynamics

Physical activity contributes to energy deficit through both direct energy expenditure and indirect effects on metabolism and body composition.

Aerobic Activity

Running, cycling, swimming, and similar activities typically expend 5-15 calories per minute, depending on intensity and body mass. Aerobic activity improves cardiovascular efficiency and supports metabolic health.

Resistance Training

Resistance exercise typically expends 4-8 calories per minute during the activity itself. The primary physiological value lies in the preservation or development of lean mass, which maintains resting metabolic rate during periods of caloric restriction.

Incidental Activity

Non-structured movement throughout the day (NEAT) may account for 15-30% of total daily energy expenditure. This component is highly variable between individuals and can be deliberately increased through conscious movement integration.

Time-Dependent Changes in Energy Balance

Short-term deficit (days to weeks): During the initial phase of caloric restriction, the body primarily draws upon glycogen stores and increases lipid oxidation. Hormonal adaptations begin but are not yet pronounced. Weight loss during this period reflects glycogen and water loss more than adipose tissue loss.

Chronic deficit (weeks to months and beyond): Extended energy restriction triggers more substantial metabolic adaptations. Hormonal changes become more pronounced, including sustained reductions in thyroid hormone levels. NEAT spontaneously decreases as the body conserves energy. The rate of energy expenditure reduction may slow weight loss progression over time, despite maintenance of the caloric deficit.

The transition between these phases occurs gradually, typically within 2-4 weeks, though individual variation is substantial.

Common Physiological Adjustments Over Time

- Reduced resting metabolic rate: Basal metabolic rate decreases, typically 10-25%, though the magnitude varies considerably between individuals.

- Increased hunger perception: Leptin reduction and ghrelin elevation intensify appetite signaling, making adherence to caloric restriction more challenging.

- Enhanced metabolic efficiency: The body becomes more efficient at extracting and utilizing energy from food, reducing the thermic cost of digestion and activity.

- Changes in substrate utilization: The body shifts toward increased reliance on fat oxidation, with reduced carbohydrate oxidation, particularly during low-intensity activities.

- Alterations in body composition trajectory: While total weight loss may continue, the proportion of lean mass lost may increase relative to adipose tissue loss as the deficit persists.

- Spontaneous activity reduction: Unconscious reductions in daily movement and spontaneous physical activity occur as part of energy conservation mechanisms.

- Hormonal shifts: Sustained changes in thyroid hormones, cortisol, and other endocrine markers reflect the body's adaptation to prolonged energy scarcity.

Links to Supporting Articles

Explore in-depth explorations of specific aspects of energy deficit physiology:

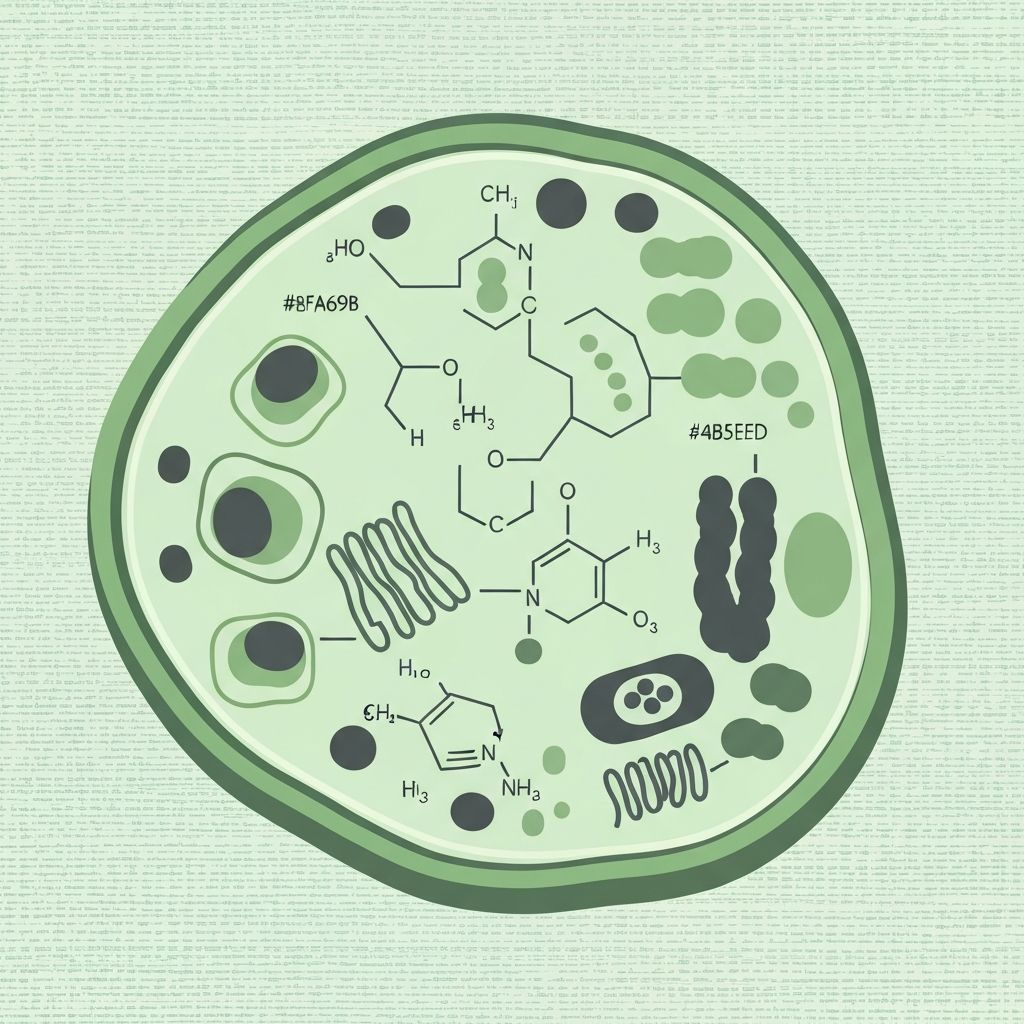

Metabolic Biochemistry

Detailed examination of what happens metabolically during an energy deficit, including substrate utilization and enzymatic changes.

Read the full scientific explanationAdaptive Thermogenesis

Research-based summary of how the body conserves energy through metabolic adaptation during prolonged caloric restriction.

Learn more about the physiologyNEAT and Activity

Exploration of non-exercise activity thermogenesis and its role in overall energy expenditure and deficit sustainability.

Explore supporting researchProtein and Energy

Scientific context for protein intake and its role in preservation of energy expenditure during energy deficit.

Continue to related topicsLong-Term vs Short-Term

Comparative analysis of physiological differences between acute and chronic energy deficits based on research data.

Read the full scientific explanationHormonal Responses

Overview of endocrine adaptations and hormonal changes during sustained energy restriction.

Learn more about the physiologyFrequently Asked Questions

How quickly does the body adapt to an energy deficit?

Metabolic adaptations begin within days but become more pronounced over weeks and months. The initial phase (1-4 weeks) primarily involves glycogen depletion and water loss. More substantial metabolic changes, including reductions in thyroid hormones and spontaneous activity reduction, typically emerge after 4 weeks of sustained deficit.

Does metabolic rate permanently decrease during an energy deficit?

Research indicates that metabolic rate reductions during energy deficit are largely reversible upon return to adequate energy intake. However, the rate of recovery varies among individuals, and some studies suggest lingering adaptive thermogenesis may persist for weeks following resumption of normal intake.

What determines how much metabolic adaptation occurs?

Individual variation in adaptive thermogenesis is influenced by multiple factors including deficit severity, baseline metabolic rate, genetic predisposition, previous dieting history, physical activity levels, and nutritional composition. Some individuals demonstrate substantially greater metabolic adaptation than others.

Is metabolic adaptation the same as "metabolic slowdown"?

Adaptive thermogenesis refers specifically to the reduction in energy expenditure in response to deficit. While related to colloquial descriptions of "metabolic slowdown," it is a distinct, measurable physiological phenomenon supported by extensive research rather than a folklore concept.

How does physical activity affect metabolic adaptation?

Regular resistance training may attenuate the loss of lean mass during energy deficit, thus partially offsetting the metabolic rate reduction that would otherwise occur. Aerobic activity contributes directly to energy expenditure but does not substantially prevent metabolic adaptation itself.

Deepen Your Understanding

Explore the broader landscape of human energy balance and metabolic science through our comprehensive article collection.

Continue exploring energy deficit concepts